The Dead House

By Adrian Cook, Architect

The Boughrood Dead House is the product of a unique set of historical circumstances, and is thought to be the only Parish Mortuary to survive in Wales. It dates from the mid-1850s, while the church was being rebuilt. The young, rich Henry de Winton had recently succeeded his father as Rector and flung himself into his parish duties with a fervour that his father had never shown. He pulled down the crumbling medieval church and built the church one sees today as a memorial to his parents, designed in the Geometrical style by C. H. Howell.

A few years earlier, new laws had initiated and encouraged the construction of buildings in churchyards and burial grounds to house bodies before burial, partly as a public health measure. In 1854, an outbreak of cholera in Brecon, a mere 10 miles away, caused great local concern, and there were 57 deaths between October and December of that year. Henry de Winton had stonemasons on-site for the church, and saw it as his philanthropic duty to take the opportunity to provide the most up-to-date facilities by adding such a ‘reception house for the dead’ at Boughrood. At that time, it was believed that cholera was spread from contact with a corpse or from breathing the miasma the corpse produced. Scientists and medics were agreed that the only way to prevent an epidemic from spreading was to ensure that bodies were removed from the home as promptly as possible. Two years later, however, Dr John Snow demonstrated that cholera was spread through sewage in the drinking water rather than by the presence of a corpse, so Henry’s well-intentioned gesture was not followed up elsewhere in Wales, as he had probably hoped it would.

Dead Houses and Mortuaries

As urban populations rapidly grew in the mid-1800’s, it became clear that existing churchyards and burial grounds were inadequate to house the dead, and that new approaches to burial were needed. At the same time, the middle and upper classes of Victorian society were developing new ideas about death, often highly decorous and accompanied by romantic sentimentality, in contrast with the more matter-of-fact approach of their forebears. These forces came together in a series of Acts of Parliament that transformed burial practices over the course of the century.

One of the issues that concerned the reformers was the traditional custom of keeping corpses at home prior to burial. In wealthier households the body would be carefully prepared for viewing, kept in a special place away from the everyday life of the family, and then viewed under highly controlled conditions for a limited time. The bereaved friends and family would be able to pay their respects and express their feelings, but the process was kept as far as possible within the bounds of social decency. By contrast, their poorer neighbours were unwilling or unable to adopt these rituals, and would keep the corpse in their most often small, ill-ventilated and crowded dwellings.

A further concern was that provision should be made for corpses to be examined before burial, for evidence of a crime, by a doctor to better establish the cause of death, or occasionally to confirm that the body was really dead – there had been quite a few cases of unexpected revivals and premature burial. These inspections and examinations would be most easily done in a separate mortuary set up for the purpose.

The Metropolitan Interments Act of 1850 commented on the desirability of “sending bodies of the dead to reception houses before internment”, and was followed by the 1852 Metropolitan Burial Act specifically allowed to provide “fit and proper Places in which Bodies may be received and taken care of previously to Interment, and to make Arrangements for the Reception and Care of the Bodies to be deposited therein.”

In 1853 a further Act extended the provisions of the 1850 and 1852 Acts to the whole of England and Wales.

Despite all this worthy and well-intentioned official concern, churches did not all rush to build Dead Houses. They had no powers to demand the body to be delivered to them, and no additional funds to look after it when it was, so they had little incentive to press hard to quickly remove bodies from the family home. No new money was provided to pay for the new buildings; churches were expected to find the money themselves, or would need a wealthy donor to come forwards, like Henry de Winton in Boughrood.

Counter-arguments were presented to justify the traditional custom of keeping the deceased at home to allow family and friends to visit and assuage their grief. The cost of a respectable funeral was a considerable outlay for the less well off, and many families needed time to get the money together. Another consideration was that working people could only gather for a funeral on Sundays, so if the death occurred towards the end of the week, they might have to wait until the following Sunday for the burial.

In practice, the strongest and most pressing argument for providing Dead Houses or mortuaries was on the grounds of Public Health. In the larger cities there was growing acceptance of the need to provide at least a basic holding facility for use during epidemics or emergencies, and Coroners’ juries pressed for mortuaries to be provided, preferring not to regularly sit with a decaying corpse in the crowded room of an impoverished family. This was less of a problem in rural areas, which helps to explain why Boughrood’s Dead House is such a rare thing to appear in a country churchyard.

Bier Houses

The date of the Boughrood Dead House is strong evidence that it was built to meet the needs identified in the Burial Acts, and in particular to respond to the 1855 cholera epidemic. However, it is also closely related to the Bier Houses that are more commonly found in rural and urban churchyards alike.

The Bier House was not as cheerful an establishment as it sounds. Most parishes had a bier, used for transporting a corpse on its journey from the home (or church gate) to the graveside. As the vehicle for the journey from one life to the next the bier carried considerable symbolic significance, but it was generally a simple, practical object. It was a wooden frame with four handles, often fitted with wheels where the roads and pathways were good enough. This did not apply in Boughrood – the surviving bier stands on four legs.

In many churches the bier was stored above head-height in the lych-gate when not in use, as it is at Llanstephan. The lych-gate was the traditional entry point for the corpse into the churchyard. Some churches had small buildings of wood or masonry to house the bier, usually in a corner of the churchyard near the entrance. These Bier Houses, of which several survive, could sometimes double as Dead Houses when needed, with the body kept in isolation if considered infectious, or laid out for visitors to pay their last respects.

Boughrood’s Dead House fulfilled the additional functions of a Bier House, and once the threat of cholera had receded and normal church customs were established, it could easily be mistaken for one.

The Building and its History

The view from outside the east gate, with the Dead House on the right, tucked into the corner of the churchyard.

Diamond Leaded Lights

The Dead House is situated in the northern corner of the churchyard, at the furthest point from the modern village and the two main churchyard gates. The intention appears to have been to tuck it away as far as possible. The traditionally favoured place for graves was on the south side of the church, and particularly alongside the paths to the church door; the Dead House was kept well away from this area. Its handsomely built windows and doors show that it was not ashamed of its appearance, so it was presumably held at arm’s length largely from fear of contagion and smells.

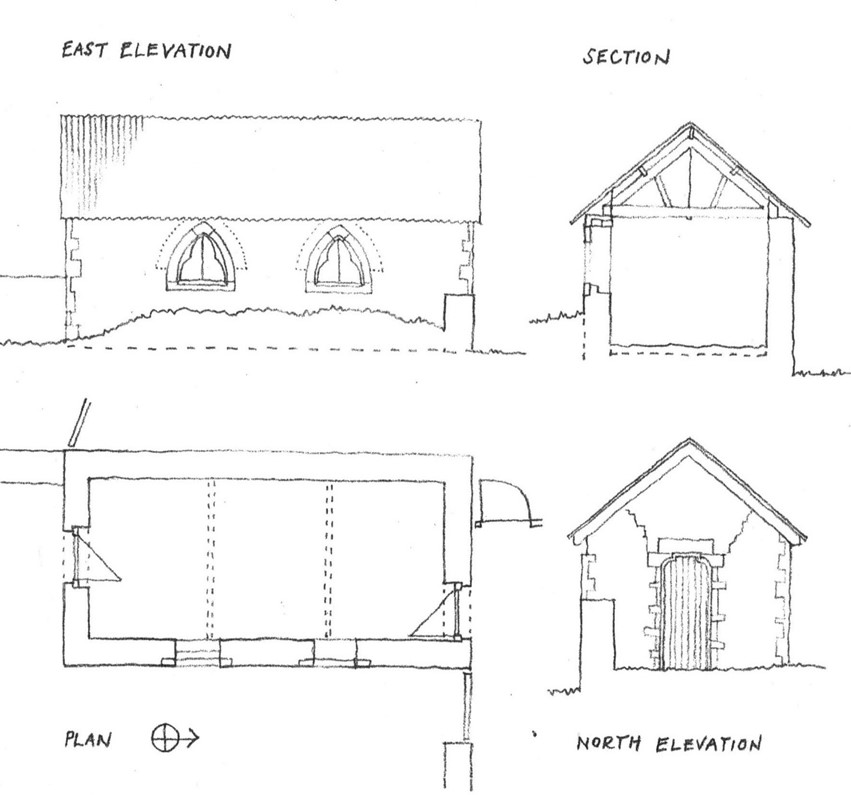

The building, which runs from north to south, has two matching doors at opposite ends. The north door, through which the body would enter, is on the roadside. Later, when ready for burial, the body would leave by the south door and was carried on the bier to its final resting place in the churchyard. The space inside the building was just large enough for the bier to be placed in the centre, with room for the living to move around it on all sides, view the body, and prepare it for burial. Two windows on the east side allowed some light into the interior, but were glazed with obscured glass to keep it safe from prying eyes.

The walls of the Dead House were evidently built by the same stonemasons who built the church and the front of Henry de Winton’s Rectory. The corners (quoins) and the door and window surrounds are of limestone (Bathstone), accurately cut and carved with elegant cusped arches to the windows. The infill walling is random rubble masonry in local stone. The best quality walling was given to the sides facing the churchyard and road; the back side was rougher, and left very plain.

Although modest in size and status, the building was given the honour of a simple ‘Gothic’ appearance, conforming to the style and architectural language of the church itself.

Simple Gothic Appearance

For purely practical purposes it could have been a very simple shed, but it was decided that the building merited more than that. The architectural treatment was no doubt partly due to it being built by the church stonemasons who happened to be on site, but it can also be seen as a statement by Henry de Winton that this gift to the Parish had a purpose that went beyond the purely practical, and that it should be viewed with due decorum and respect. It is likely that his ‘Dead House’ was a finer building than the turf-walled cottages of many of the living rural poor at that time.

The windows had diamond leaded lights, glazed with ribbed obscured glass. This was a radically new industrial material at the time. It was made by the rolled plate glass process, developed in 1847 by James Hartley, and often used for the roofs of railway stations and greenhouses. The doors are more traditional, with a good chunky Victorian lock on the south door that still works cleanly today after a century and half of exposure and many years of neglect.

Exit door for the Bier & Deceased

For as long as anyone can remember, the building had a corrugated iron roof, pitted and failing with age. It is quite possible that this had been in place for the majority of the building’s life, but unlikely that it was original. Archaeology during excavations for the restoration found fragments of clay tiles similar to those on the church, and inspection of the original roof timbers showed evidence that roofing battens (for slates or tiles) had once been in place. The most likely course of events appears to be that it was originally roofed in clay tiles to match the church, and then re-roofed in corrugated sheeting when the tiles failed, to save on the expense of repair.

The roof trusses included a vertical iron bar in the centre, replacing the traditional timber king post. Like the obscured glass, this is an example of 19th Century technology being used in what appears at first sight to be an entirely traditional medieval-style building.

The internal finishes were very plain. Archaeology revealed no evidence of any stone or tiled flooring, so it must have had an earth floor. There is no sign of any whitewash or plaster remaining on the internal walls, which must have been plain rubble walling. At the higher levels of the walls the masons gave up any pretence of decorum, completing the walls with building detritus – broken fragments and offcuts of discarded Bathstone. Clearly the external appearance of the building was felt to be much more important than the interior. Its rough plainness would not offend the dead, and perhaps the feelings of the poorer families who were most likely to visit were expected to be similarly robust.

Once built, the Parish took to the Dead House and it was used as intended to prepare the body for burial and hold the bier. Coffins would generally be brought to it the day before the funeral which, from outlying parts of the parish such as Cornhill and Boughrood Brest, entailed a long and often muddy journey. If the coffin were already at the churchyard, the funeral clothes of the family could remain clean and presentable. The last time that the Dead House is known to have been used for its original purpose was in 1928.

Historic graffiti

Historic graffiti can still be seen carved into the door and the surrounding stone on the north side of the building. It seems that it was more acceptable to deface the wall facing the road than the walls within the churchyard.

Neglected for many years

At some stage in the early life of the building a pine tree was planted just in front, soon casting sepulchral shadows over it, and later obscuring it almost entirely. Gradually its roots undermined the building’s foundations, and the weight of its discarded needles damaged the roof.

By the 21st Century, the Dead House was in a very poor state, having been neglected for many years, its original purpose largely forgotten. Earth had been piled up against it, large and widening cracks were appearing in the walls, timbers were rotting, and the roof, already full of holes, was in danger of collapse.

A drawing of the Dead House before Restoration

At the last, its value was recognised, and a project was begun to revive and restore it.

Restoration

Interest in the Dead House was revived when the large pine tree in front of it was felled, revealing what had, for so long, been hidden. Its purpose and unique history were recognised, and the ambition to restore it was kindled. In 2012 it received a Grade II listing, and was noted as a building ‘at risk’. The Parochial Church Council agreed to start a Restoration Project for the Dead House, led and inspired by the Revd. Ian Charlesworth, with fundraising and project management spear-headed with tremendous energy by Elizabeth Bingham, backed up with great support and imagination by many others in the parish.

In the early stages of the restoration project, attempts were made to find alternative uses for the building. Might it serve as a meeting room for the Parish, or be used to exhibit local history? Was there a way to extend it, adding facilities for the church? It eventually became clear that none of these ideas could be made to work: they were too expensive, the structure and setting were too historically sensitive, and the building was too small. It would be inappropriate to use it for a WC or for simple storage, or to radically change its character. It was therefore decided to restore the building as it was – as the ‘Dead House’.

Money was needed. Heritage Lottery Wales was approached, and was supportive of the general idea of the restoration. After an initial ‘Stage 1’ bid, they provided some funding to develop the design and specification and to work out the detailed costs. These were then submitted in a successful ‘Stage 2’ bid, which secured funding for the great majority of the project costs. Without their generous support, the restoration would not have been possible.

The Community Fund in Wales kindly provided a significant sum towards professional fees.

Significant local fundraising was also needed. Two fundraising concerts were held in the church, one of which featured Revd. Charlesworth singing comic songs in inimitable style. Alongside some generous local donations, a talk was given by Valerie Singleton, there were coffee mornings, an auction of donated goods, and over £1000 was raised from local residents and friends at the re-opening party for Boughrood Toll House.

The Lottery Fund encouraged local activities to raise interest and awareness. These included two significant school projects. Children from Archdeacon Griffiths School in Llyswen made a film about Boughrood in the 19th Century, covering the cholera epidemic in Brecon, safe sewage disposal in Boughrood, parish relief, Hay workhouse, cider-making and addiction. They also made a model of a 19th Century churchyard, with table-top tombs for the wealthy and respected, a grand memorial for the Jones Family, headstones, and a communal pit for the paupers. Making pauper skeletons was very popular with the children. Making worms for the pit threatened to prove equally popular, but was, for some reason, discouraged.

Approval (a ‘Faculty’) was required from the Church authorities, advised by their expert Diocesan Advisory Committee, and also Listed Building Consent from Powys County Council.

The PCC appointed Adrian Cook as Architect and Chris James (Chris James Stonemasonry) as the Contractor. While fundraising was underway and the project was being developed, the decay of the building seemed to be accelerating. The cracks in the walls were opening ever wider, and the roof was collapsing. Chris did some emergency propping, and covered the roof with a tarpaulin, until work was ready to start on site in the autumn of 2018.

Chris James, Contractor, propping up the props.

At an early stage, trial pits were dug to work out why the walls were moving so much and what could be done about it, and the build-up of internal detritus was removed. Neil Phillips of APAC Ltd carried out archaeological surveys throughout the project and found little of interest, which was a great relief. Unearthing ancient ruins or medieval corpses would have been a nightmare for the timetable and the budget.

Neil Phillips of APAC Ltd carried out archaeological surveys throughout the project

Walling – The south-east corner of the building had been worst affected by the tree roots, and was falling away from the building. This corner had to be rebuilt up from a secure lower footing, from the east side of the south door to halfway along the east elevation, including one of the windows. This section of wall was carefully dismantled, with individual stones photographed and numbered to go back exactly in the right places. A suitable lime mortar mix was used, coloured to match the original as far as could be achieved. Bad cracking in the opposite corner was addressed by inserting concealed steel anchors inside the wall to hold it together. Broken and damaged pieces of dressed stone (including one side of the north window) were either repaired or skilfully replaced with new matching Bathstone. Rotten timber lintels and wall-plates were replaced. Internally, areas of loose stone were repaired at higher levels of the wall, but the temptation to repoint and tidy everything up was resisted.

The restored east wall. The left side was rebuilt from below the ground. Part of the stone surround of the right window was renewed.

Roof – The main timbers of the two roof trusses proved to be too rotten to restore, so new trusses were created to match, re-using the original side struts and central iron tie-bars. The rest of the roof structure (purlins, common rafters and tile battens) was constructed in new sawn Douglas Fir. This gives a plain but pleasing appearance to the underside of the roof viewed from the interior. The handmade clay roof tiles are a random mix of three colours, attempting to match the colours of the fragments of tile found around the building, and also relating to those remaining on the church roof. The remnants of chamfered timber bargeboards on the ruined building allowed for accurately sized replacements to be made.

Rotten roof trusses.

The roof under construction.

Windows & Doors – The leaded lights of ribbed glass were recreated by stained-glass specialist Simon Howard on the basis of a few surviving original fragments. The doors needed remarkably little repair, apart from some rotten boards at the base. The original door key was still in place, but no spares. A modern locksmith can’t cope with such a key, so copies were cast in the traditional way, just in case.

The north window before restoration, with a few surviving fragments of glazing, and a crumbling stone on the left.

The restored window, with the original door key.

Floor – This is the one aspect of the restored Dead House that is significantly different from the original building. Retaining an earth floor would have been cheap and easy, but it was felt that if anything might be upgraded, this was it. When Revd. Charlesworth pointed out that there were a number of displaced gravestones lying along one side of the churchyard, this was realised to be a great opportunity for the project to add something of value to the building. These stone slabs no longer marked graves, and would otherwise be left to weather away unseen. Some of them had good quality carvings and commemorative inscriptions. A selection was made, and considerable manpower was deployed to lift and move them, to be carefully laid out to form the new floor. In this new setting their visual qualities and memorial role can be properly appreciated, adding to the funerary character and atmosphere of the building.

Restored Floor & Bier

The Bier – The Parish Bier is once again housed in the Dead House, still in one piece, but needing restoration and repair if it is to ever again be trusted to carry a coffin.

The restored Dead House was re-opened on Hallowe’en 2019. A celebratory event, simultaneously fun and sinister, was held at the church, attended by about 150 people. Ian Charlesworth and Jim Beagley, a parishioner who works in special effects for films, jointly designed a spectacular event with a fifteen-foot flare sending out jets every few minutes, the church bathed in red light, mist enveloping the churchyard, and a mass of candles illuminating the Dead House (attracting, appropriately, clouds of flies). Mulled cider and nibbles were served. Danse Macabre was played on the organ before a spot-lit Ian Charlesworth, standing in front of the church porch, described some of those buried in the church yard – Mary Powell, run down by a shunted railway engine; Jeremiah Price, who died in the Hay Workhouse Hospital; an unknown woman found dead from starvation beside the Bach Howey; the six children of ten from the Cilgwyn who died young; and Henry de Winton, Rector, who built the church and the Dead House. As he described each person, a spotlight shone on their ghosts, emerging from behind their gravestones. Some of the ghosts, still in their make-up, were later seen haunting a local hostelry.

Hallowe’en 2019.

Within a few months of this great event, Covid-19 gripped the world, bringing home the realities of life in a pandemic, which had, in an earlier age, inspired the building of the Dead House. Shortly afterwards, the Revd. Ian Charlesworth passed away. Without his vision and enthusiasm, the project would not have happened, and the building could have been lost forever. The new life brought to the Dead House is a fitting part of his legacy to Boughrood.

The Exterior of the Restored Dead House

The Interior of the Restored Dead House