Hay Union Workhouse

This is an edited article from an original by Dr Peter Ford.

The Poor Law

From feudal times Vestry Committees in every parish were responsible for administering not only the running of the church and appointment of its officers, but also civic affairs such as law enforcement, maintenance of roads and control of vermin, and support for the poor and suppression of vagrancy.

The Poor Relief Act 1601 enabled vestries to tax property owners to raise money to support the poor of the parish. Some workhouses were established but this was expensive for the parish and there were very few in Wales. Most help was in the form of a subsidy for those on a low wage known as ‘out relief’, and covered such things as money, food, cloths, blankets and fuel, which allowed the poor to continue to live in their own homes. Where workhouses did exist, there was a great deal of variation in conditions: some were little more than boarding houses where inmates lived and left to go to work each day. Local farmers were paid to supply meat for inmates each day, for which they were paid. Some workhouses even had shops for inmates. The workhouses were paid for from the taxes of property owners, who became increasingly express a view that for many paupers the workhouse encouraged importunate marriages, large families and removed any incentive to work.

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 (in which year the average poor-rate expenditure was £5,492 or 9s 8p per head) was brought in to counter this by consolidating previous legislation and relieving vestries of their responsibility. A Poor Law Commission was set up to oversee a new way of providing poor relief, which established a national system by grouping parishes and linking them to specific workhouses. Conditions in workhouses were designed to be deliberately harsher than labouring work so that only in dire circumstances would people resort to parish relief. The health of inmates was of little importance, the key driver was to keep costs down. Due to the harsh regimes the poor did not like them and a number of workhouses were the object of attacks during some of the Rebecca Riots between 1839 and 1843 in west and mid-Wales.

Hay Union Workhouse

Four workhouses were set up in Breconshire, in Hay, Brecon, Crickhowell and Builth Wells. The Hay Workhouse was built in 1837 opposite St Mary’s Church, and is now converted to private dwellings. The Hay Poor Law Union covered 25 parishes in three counties with a population of 11,403 in 1831: in Breconshire – Aberllynfy, Bonllys, Glynfach, Capel-y-fin, Hay, Llanellieu, Llanigon, Llyswen, Pipton, Talgarth (including parishes of Borough, Forest, Trefecca, Pwll-y-wrach), Tregoyd, Velindre; in Radnorshire – Bettws Clyro, Boughrood, Bryngwn, Clyro, Glasbury, Llanbedr-Painscastle, Llandeilo Graban, Llanstephan, Llowes; and in Herefordshire – Bredwardine, Cusop, Clifford, Dorstone, Whitney.

Hay became the site of the workhouse as many of the parishes were very small, whereas Hay had 1,959 inhabitants and was the main centre of population. Hay Union Workhouse, known as The Union or Spike, opened in 1837 on 4 acres of land purchased from James Spencer, the notorious local solicitor. It was built to provide relief to ‘law abiding paupers’ as well as widows, children and the disabled. The building cost £3,200 and originally was only meant to house 15 inmates. Extensive additions and alterations were made in subsequent years to enlarge it and bring it up to the required standard. The design was a typical cruciform shape with a central administrative core and 4 radiating arms, one each for males, females, infirm and able-bodied. The whole was bounded by railings and iron gates.

Hay Poor Law Union

To administer the workhouse and care for the poor a Board of Guardians was set up consisting of 27 local ratepayers. They appointed a surgeon and clergy to provide support to the inmates, and a master and matron to run the workhouse. In 1859 the officers of the Poor Law Union in Hay were:

Chairman Rev. Richard Venables

Governor George Jones

Matron Elizabeth Jones

Clerk to the Board of Guardians Thomas Lewis

Surgeons Henry Proctor and William Williams

Registrar John Lloyd

Relieving Officer Thomas Gwynne of 16 Broad Street. In addition there would have been a chaplain appointed. After Richard Venables left Hay the Rev William Lathan Bevan was appointed and held the post for many years. No treasurer is mentioned among the officers but there was an advert for one in 1858 to replace Thomas Prothero Price who had resigned. This was a necessary post as half yearly visits were made by the district auditor to check the accounts.

The clerk to the Governors was Thomas Lewis, one of the original appointments made in September 1836. He finally retired in January 1860 after 23 years service. His replacement ,Charles Griffiths, was still in post in 1897.

The officers were always conscious that they needed to keep expenditure to a minimum. An advert for a medical officer in 1897 offered a salary of £21 a year, just £1 more than the nurse, although of course it was only a part-time post.

The 1851 census records Edward Powell as Master and he was still there thirty years later at the age of 57. He was the son of farmer Thomas and his wife Elizabeth of Lower Boughrood Court Farm. The matron was Edward’s wife Rebecca aged 45years. The servants were Mary scott, a nurse in the infirmary, and Mary A. Harper, the cook.

In 1850 a nurse post was advertised in the Hereford Times for a middle-aged female – ‘none need apply who cannot read writing’ so this was probably Mary Scott. It is not known how long she was there but her replacement appears to have been Mrs Mary Prosser because she was replaced due to illness in 1857. A single woman or widow with no dependents was required who ‘must be able to read medicines supplied to inmates of the hospital’. Salary £25 Another advert in 1867 was for a similar single or widowed woman. The salary offered was only £15 but in addition rations, coals, candles, washing and a furnished apartment were offered. A ‘knowledge of midwifery’ is described as indispensable.

Provisions

Only one advert for a baker, dated 1861, has been discovered. This was a whole-time post at 15 shillings (75p) per week. The advertisements for quotations to supply provisions to the workhouse later included the supply of bread, so this post may have been short lived. A local Hay inhabitant, Neville Jones, remembers delivering loaves to the workhouse premises in the early 1960’s.

Regular advertisements were placed for tenders to supply foodstuffs and goods to the workhouse. In 1850 the tender was just for flour but in 1853 meat was included and quickly a number of other items were added. A tender invitation from September 1953 was:

For 3 months at the quantities required.

Flour, best seconds

Beef without bone and with bone

Mutton, breasts and neck without bone and with bone

Beef kidney suet

For 6 months at the quantities required

New milk at imperial quarts

Yeast at imperial quarts

Beer and porter at imperial pints

Brandy (best French)

Grocery, the several articles required

Coals best Welsh per ton

An additional item in all tenders was the provision of coffins of elm or alder boards 7/8 inch thick (later reduced to ¾ inch) together with shrouds, letters and cords. This regular item on the tenders indicates that deaths in the workhouse were a regular occurrence. The poor were normally interred in unmarked communal grave plots and this included inmates from the workhouses. Periodically the tender included unspecified clothing and shoes for men and women.

An advertisement of October 1861 for one ton of Gloucester cheese to be supplied as and when is the only one discovered naming this basic commodity. The provision of best French brandy also appears throughout the century, but whether this was for the inmates or the Guardians is a matter of conjecture.

By 1893 tenders were more specific although the flour, meat, suet, beer and porter, brandy, coal and coffins were unchanged. Additional items included bread, that had to be 4lb loaves no more than 24 to 48hours old, grocery as listed, and a variety of items including soap and candles. Peas by the quart were always listed and seem to have been a major constituent of the workhouse diet. Beer and porter were dietary staples at this time even though they had their own water supply from a well in the grounds. It would have been used primarily for washing and cooking.

Inmates

Once the buildings were enlarged the number of inmates increased from the original 15 to around 50, although this was subject to variation. There were an equal number of males and females in 1861. Approximately one third of these were young children, although families were split up which was a further sign of degradation to inmates in the system. Inmates were free to leave of their own free will, and a number did when offers of work or other circumstances permitted.

The 1861 census listed 54 inmates but it is interesting to note that despite the large catchment area of the workhouse less than 6 came from a greater distance than 10 miles from Hay. These were from Ross, Llandrindod, Llandeilo and one female from London. The presence of someone from London is interesting as the workhouse was paid for by the parish and there were strenuous attempts to make sure anyone admitted did not belong to another parish. Later advertisements required separate tenders for the districts of Hay and Glasbury, even though Glasbury was within the Hay Union so this may have been for the outdoor-poor.

In March 1861 overseer Mr John Stephens of Sheephouse applied for an order to remove Elizabeth Williams and her three children from the workhouse to her ‘place of settlement’. Her mother Mrs Ester Jones testified that this was at Clifford and the Order of Removal was granted. Later in August of the same year another overseer Mr Tasker went to court to obtain the removal of William Pritchard aged 72years from the workhouse. Pritchard was born around 1789 at Llanigon. Aged 14 he went to work for Mr Spencer at Sheepcot Clifford. Shortly afterwards he returned to live with his father in the family house at Llanigon and did not work again. The magistrates ordered that he be discharged to Clifford, which being in Hereford was in a different union, for support.

The 1861 census return listed Charles Fowke of Boughrood Castle, a widower aged 57, who was described as a former gentleman. Charles was the youngest son of Francis Fowke and maintained he did not receive his fair share of his inheritance, which may account for his stay in the workhouse. He was eventually rescued by his irritated siblings and packed off to his sister in Australia on board the Queen of the Colonies in October 1865.

In 1863 Pitt Price, a mason’s labourer, was prosecuted by the Board of Guardians for not maintaining his wife Emma and his infant child Emma Blanche, who had become chargeable to the parish and consequently had been admitted into the workhouse. Price admitted failure to pay and ill-treating his wife and promised to treat her better, pay future maintenance, and pay the 8 to 9 shillings (40-45p ) cost of the proceedings.

Another inmate was Mary A. Price. She was shown in the 1851 census to be a laundress at Boughrood. By the 1861 census she was a mason’s widow with two daughters aged four and five years still living in Boughrood. By 1871 Mary, at the age of 38 years, was in the workhouse and there is no mention of her daughters. She was still there in 1881.

All able-bodied men were required to work, breaking stones for road making in the cellar at the workhouse or picking oakum, while women had to attend to washing and cleaning. Oakham picking involved unpicking tarred hemp cables that were too rotten to use on ships. When broken down into loose fibres the oakum was used as packing between ships planks to caulk them and make ships watertight. A spike was used to push into the ropes but due to the tar it was very difficult and hard on the fingers and hand. Everyone hated it.

Not all those eligible necessarily applied for relief, and the Radnorshire Constabulary Records give an account of an unknown woman found in the Llanbach Howey Brook, Llanstephan, who had died of starvation.

Standards in the Workhouse

Generally, Hay’s institution maintained a high standard according to the government Inspector. However, there was a problem in 1864 when Joseph Rowntree made an inspection. His report was highly critical of the system and he highlighted a large number of deficiencies. In particular he noted the harsh treatment of paupers, none of whom received support however destitute they might be if they were thought to have been able bodied. The relieving officer was reported to be more interested in being out hunting than attending to his duties, and his deputy was accused of illtreating vagrants.

Among Joseph Rowntree’s recommendations was to improve the food. He recommended that the piece of adjacent land rented out to the chaplain was taken over by the Guardians as a garden for produce and the keeping of pigs.

The national Committee of Council on Education took responsibility for appointing schoolmasters and mistresses in many workhouses. In the case of Hay, at the instigation of Reverend William Latham Bevan, a special gateway in the workhouse yard was provided so that the children were able to attend the adjacent National School. This was a controversial move as it was felt that mixing the children led to an improvement in the workhouse children at the expense of the education of the other pupils. The Guardians had reservations as they were more concerned with teaching the children useful skills such as scrubbing, washing, ironing, baking and needlework. Nevertheless, the Reverend William Bevan prevailed and the children received a normal schooling.

The educational standard at the school was criticised but as this improved all the children fared better. This mixing allowed workhouse children to receive an education long before the passing of the free education acts later in the century.

However hard life was at the workhouse there were attempts to provide some light relief. A newspaper report about Christmas Day 1869 notes that due to the kindness of the master and matron the children were not forgotten and a Christmas tree was provided ‘with ornamentation and useful things suitable for them’. . In July 1906 Mr and Mrs Robert Griffiths of Trewern, Cusop, hosted an afternoon outing for the inmates of the workhouse. After being shown round the pretty garden, tea was served to everyone. The children in particular enjoyed themselves ‘hay making’.

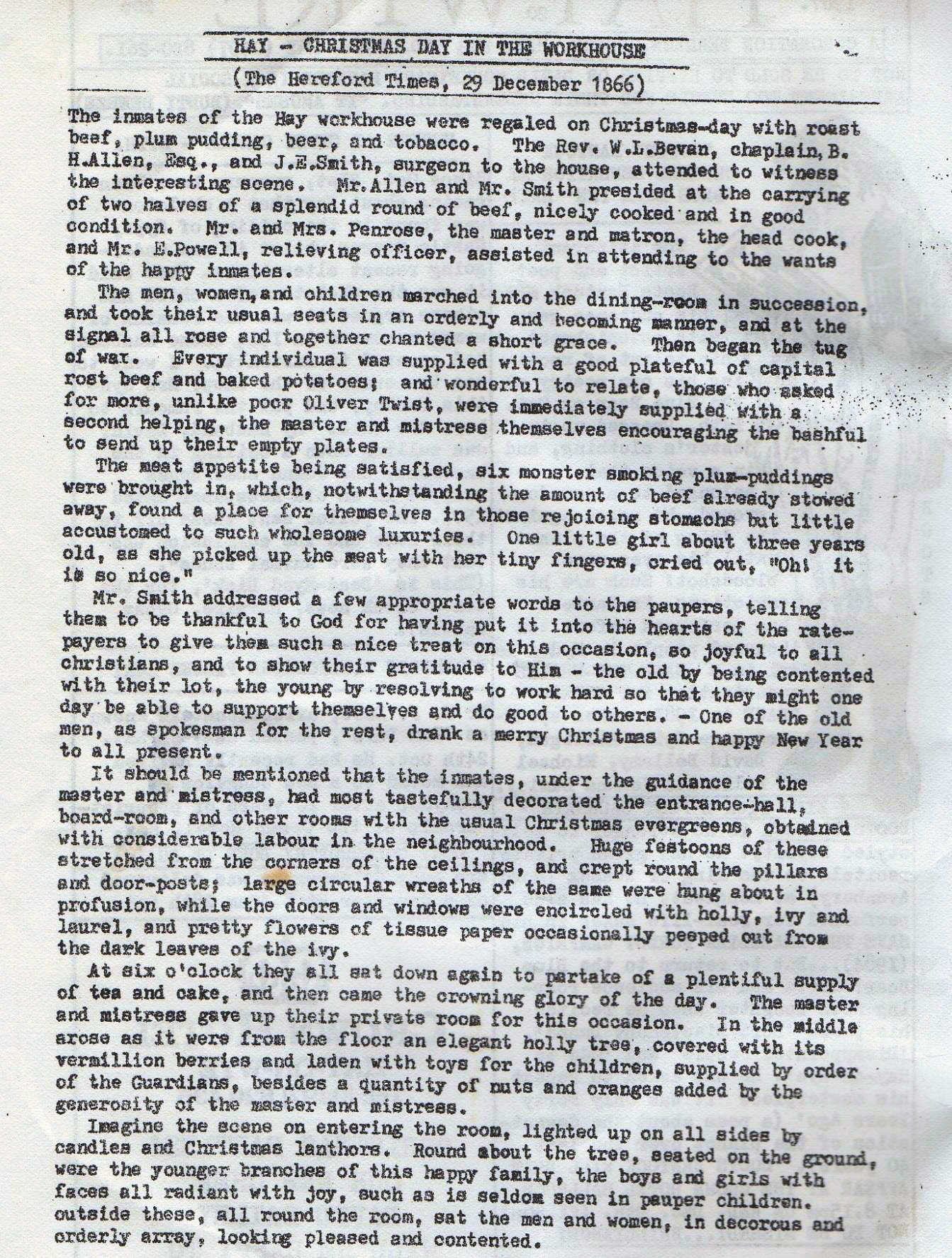

HayWire Magazine reproduced an article from the Hereford Times of 1866 which gives an account of one Christmas at the Hay Union Workhouse. While this might have been designed to present a philanthropic image to the Victorian readers of the newspaper, it shows that attempts were made to lighten the daily grind of the inmates on some occasions.

Francis Kilvert was a curate at Clyro. As part of his charity work he regularly visited the poor in the workhouse. In his diary for 1870 he found himself in charge when he visited on Good Friday. The master was away on holiday. He says he had all the inmates to himself and went through the day’s events with them.

Vagrants

The Poor Law Act was amended in 1837 to require parishes to provide a meal and one night’s shelter to anyone passing in ‘sudden or urgent necessity’ in return for performing a simple task. Essentially this was provision for tramps or vagrants known as casual poor or ‘casuals’. Initially they were put up in the infirmary as they often carried infectious disease but after a time a purpose-built, single-storey buildings were used. These were filled on a first-come first-accommodated basis. Excess applicants were simply turned away. Conditions here were even worse that in the workhouse to further discourage anyone ‘taking to the road’.

The usual system was that on entry vagrants would be searched for tobacco, alcohol and money before stripping and taking a bath. They usually would have a medical and then donned a nightshirt while their clothes were fumigated. A simple meal of bread and gruel (often called spilly) would usually be given before they were locked in dormitories. After 1864 many dormitories were changed to cells but this were not universal. Doors were locked from 7p.m. until 6 or 7a.m. when vagrants were discharged. Beds would be rugs on the floor with a blanket although women were given an iron bedstead with a blanket.

At Hay a small room by the main gates was reserved for vagrants. On the 31 July 1844 Frederick Atley, Robert Middleton and Thomas Johnson were given 10 days hard labour at Brecon County Goal for breaking the window of Thomas Perks, the relieving officer of Hay Union, on being refused relief.

This separate accommodation for the sole use of vagrants tended to be called ‘The Spike’, and the word came to be the generic term for workhouses as a whole. The origin of the name has been subject to much debate with no definite conclusion, with possibilities including: the nail used to unravel old rope to make oakum used for caulking ships; admission tickets to the workhouse were collected on a metal spike; the rough straw mattress was called a spikey; less probably it comes from the slang term spinikin used to refer to the women’s workhouse, often a spinning room where they had to spin wool; the spike or finial usually found on workhouse roofs.

Around 1900 the Hay Union Workhouse was renamed Cockcroft House after Major Cockcroft of Ty-Glyn, Cusop. Under the Local Government Act of 1929 workhouses were transferred to the County Councils and from 1930 became known as Public Assistance Institutions. While much remained the same gradually conditions improved. The most important change was that residents, as they were now called, were able to come and go as they pleased.

Later the building became a Youth Club before being sold. Richard Booth, the ‘King of Hay’, made changes by demolishing nine rooms into one large one for his philosophy and poetry bookshop. Visitors included the Reverend Ian Paisley, Denis Healy and Michael Foot who bought a book on the Romantic Poets. Subsequently it was sold and the surviving workhouse buildings have now been converted for residential use.

Hospital attached to the Union Workhouse

The workhouse had not been in existence for long before it was decided that the arm of the building used for the infirm was not adequate and it needed its own hospital. A number of advertisements were placed in local newspapers by the Clerk to the Hay Union in 1846 inviting tenders to build a new hospital. It was in six parts which could be tendered for in total or individually. These were for masons; carpenters; slaters and plasterers; plumbers, painters and glaziers; smiths work and ironmongery; and timbers. This additional building in the grounds became a general infirmary and treated patients from the local area. Jeremiah Price from Boughrood was treated here before he died in 1877. It is assumed he was conveyed back to Boughrood by train because he was buried there.

The hospital had a public mortuary attached to it. On one occasion there was a delay in transporting a body to it. To hasten events the doctor concerned dressed the deceased in outdoor clothes, sat him in the front seat of his car and ferried him to the mortuary without anyone having cause to make comment. It was not long afterwards that formal arrangements were made for post mortems to be conducted in more appropriate premises.

Peter Higginbothom has a website devoted to workhouses which is a treasure trove of information on the subject. www.workhouses.org.uk

(Please contact us if you would like more detail on source material for this article.)